BRET EASTON ELLIS

By Thierry Girandon

Translated from French by Hilary Burgess

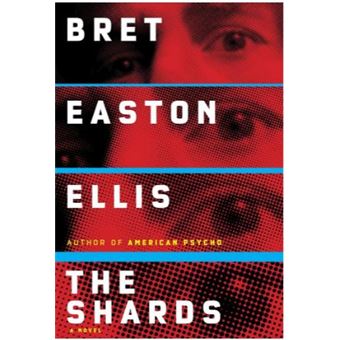

It breaks my heart to have to admit that I didn’t like Bret Easton Ellis’ latest novel at all, even though he’s one of the few contemporary writers whose books I buy as soon as they are published. My impatience to read it having been fed by everything I heard about it. Bret’s universe being the same one, but with a patina of maturity: sex, drugs and new pop music; Los Angeles as a fake enclave of the world; convertible cars, and the cry of coyotes. Time and space unchanged, the action takes place at the time Bret was writing Less Than Zero, his first novel. A portrait of the artist as a young man? a young hound? Bret says he had already had the idea for the novel, but not the maturity to write it. He had one foot still in the world of innocence and was about to step into that of corruption: his heart too tender, and his arse perched on the fence.

In the end, this substantial novel seems to me to be a summing up. We find ourselves in Bret’s kitchen amongst all the ingredients with which we, the faithful readers, are familiar. This new concoction is a potpourri of all the books he has previously written. It’s a hyperbolic rehash of Less Than Zero. The Trawler, the serial killer – the true artist of the novel – could be Patrick Bateman of American Psycho, or have escaped from one of James Ellroy’s thrillers, or perhaps from the Lars Von Trier film The House That Jack Built. He is Bret’s guilty conscience, a dream. The paranoid, schizophrenic atmosphere we found in Glamorama, the autofiction of Lunar Park. The same questions arise when reading The Shards as when reading Bret’s previous books. This killer on the prowl, is he not simply a metaphor for the work of writing? My questions are pointless, because in his book Bret Easton Ellis gives us the keys to what he is writing. He presents himself as an aspiring writer and, as such, a dreamer, a fantasist. But at the time of Less Than Zero, as a budding author torn by his conflicting admiration for Stephen King and Joan Didion, Bret was not looking backwards at what he was writing. He was writing in the present, living the numbness that he excelled at describing. “I wanted to write like this as well: numbness as a feeling, numbness as a motivation, numbness as the reason to exist, numbness as ecstasy.” As a behaviourist writer, he succeeded in coldly describing this degradation, accelerated in the yuppie era, from being into having, and the pervasive shift from having to seeming. Today, Bret moralizes, judges and comments on what he is writing as he writes it. His prose has lost some of its sobriety and speed, it is devitalized. It seems that Bret has forgotten the quote from Hamlet that he put at the beginning of Lunar Park:

« Yea, from the table of my memory

I’ll wipe away all trivial fond records,

All saws of books, all forms, all pressures past,

That youth and observation copied there “

It is a kind of novel of apprenticeship that is far too fat, with chapters that follow one another, resembling each other. The story within a story is short. Earlier, we watched the characters evolve as if from a distance, through the glass of a fish tank. In fact, there is a mention of an aquarium in The Shards, emptied of its water and fish. But now, the emptiness of these high school students appears to us in such a manner as to be dazzling. Their only value, insists Bret, is their dazzling beauty. But this moment from a life that has aged cannot be rejuvenated with bright colours. It can only be evoked in memory. In the decades that separate him from what he describes, lie the empty waters of nostalgia. Bret, now happy and fulfilled, has gone from being restless to being sentimental, and “any man whose name has been inscribed in the book of love is freed from hell”.

“THE AUTUMN I REALLY HAVE IS THE ONE I LOST”

Fernando Pesoa

Thierry Girandon is a short story writer and novelist > read more about T. Girandon

> facebook/BretEastonEllis